Digital Transnational Repression

Authoritarian governments use surveillance, online harassment, disinformation and other digital threats to silence dissent across borders. Digital technologies have given repressive regimes new tools to monitor and respond to the activities of political exiles and diasporas with greater scope and speed. In my research on digital transnational repression, I investigate how authoritarian power holders disrupt the communications and constrain the activities of opponents and critics outside their state territory. I also examine the impact of digital threats on the targeted communities of transnational activists, their strategies of resistance as well as the implications for freedom of expression, privacy and other human rights.

A recent project at The Citizen Lab focused on the security risks and harms caused by digital transnational repression against exiled and diaspora women human rights defenders. Drawing on interviews with 85 women human rights defenders from 24 countries of origin and residing in 23 host countries, we investigate the specific ways in which authoritarian regimes deploy digital technologies and weaponize gender as a tool of repression. We find that women activists and journalists face particular gender-specific forms of online harassment, abuse, and intimidation which all have a distinct political purpose: to silence criticism and dissent beyond borders. These threats lead to disproportionate harms ranging from professional setbacks, stigmatization, and social isolation to the erosion of intimate relationships, profound emotional distress, and psychological trauma

Previous research on digital transnational repression has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research program under a Marie Skłodowska-Curie Individual Fellowship (DIGIACT) and the Information Controls Fellowship of the Open Technology Fund. Key findings were presented in an essay about the toolkit of digital transnational repression that appeared in a Special Report from Freedom House, a blog post for Mobilizing Ideas, and a research report for the Middle East and North Africa program of Hivos.

No Escape

The Weaponization of Gender for the Purposes of Digital Transnational Repression

Research report for The Citizen Lab.

Silencing Across Borders

Transnational Repression and Digital Threats against Exiled Activists from Egypt, Syria, and Iran.

Research report for Hivos.

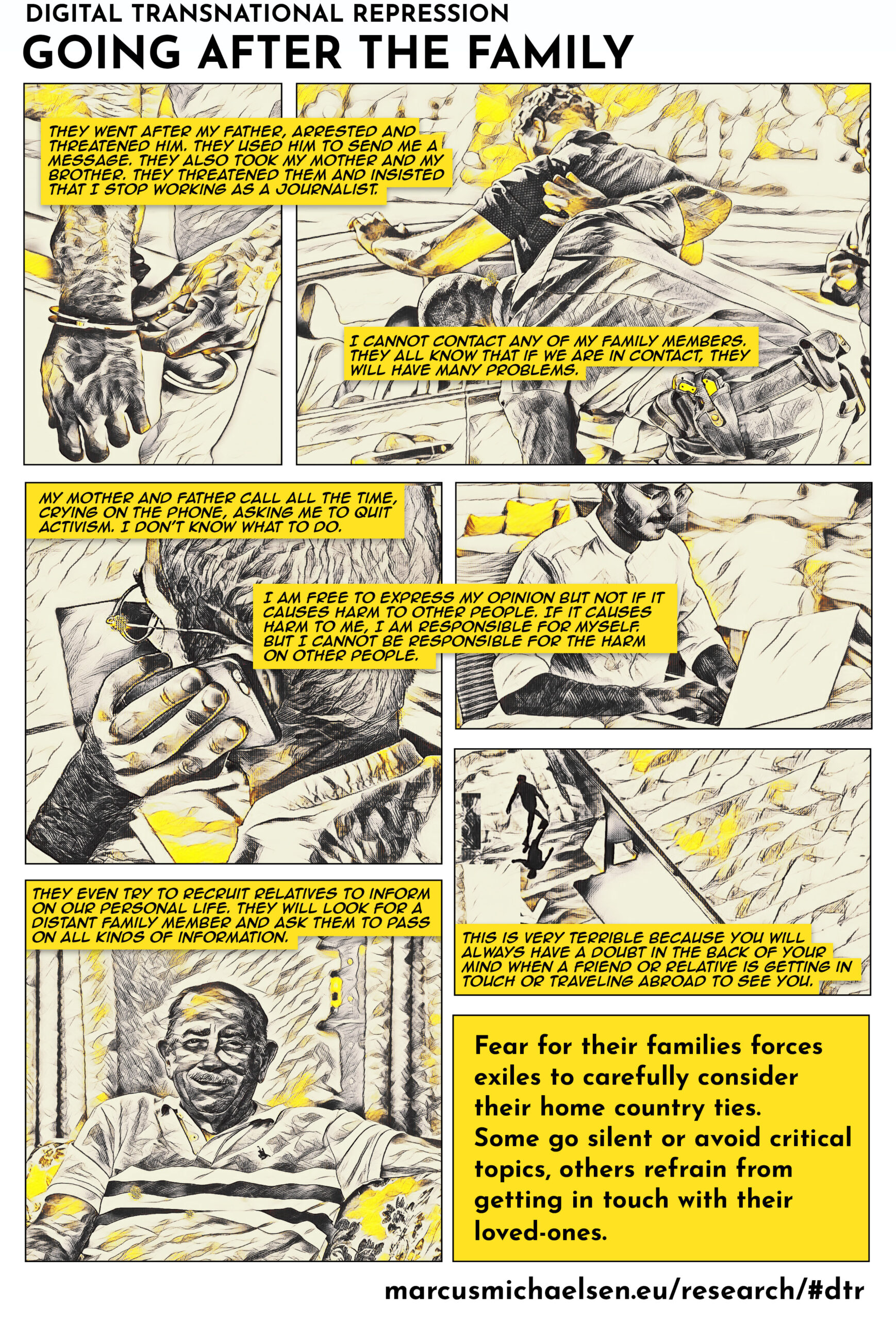

A particularly efficient and insidious method of transnational repression is to abuse family members in the home country as a means to manipulate and subjugate dissidents abroad. In a paper on ‘proxy punishment’ (co-authored with Dana M. Moss and Gillian Kennedy), we build on almost 250 interviews with diaspora activists from four Middle Eastern countries to analyze the different tactics of repression used against home country relatives and the ways activists respond to these pressures.

Research on transnational repression is increasingly interested in the role and responsibilities of the host countries of the targeted diasporas and exiles. In a paper in the European Journal of International Security (co-authored with Johannes Thumfart), we examine digital transnational repression as a potential violation of host state sovereignty. We argue that digital repression can violate host state sovereignty in that it constitutes extraterritorial enforcement jurisdiction; interferes with open debate and national self-determination; and impedes the host state’s adherence to fundamental norms of international humanitarian law. In an article for Democratization (co-authored with Kris Ruijgrok), we study how the regime type of the host country and the regional ties between the host and origin country influence the likelihood and type of transnational repression incidents. We find that to target exiles in autocratic host states perpetrators primarily rely on the cooperation of authorities, whereas in democratic host states they resort more often to direct attacks. We also show that authoritarian cooperation on transnational repression is regionally clustered: it often occurs when home and host state are situated within the same authoritarian neighbourhood, and partly also when they are members of the same regional organization.

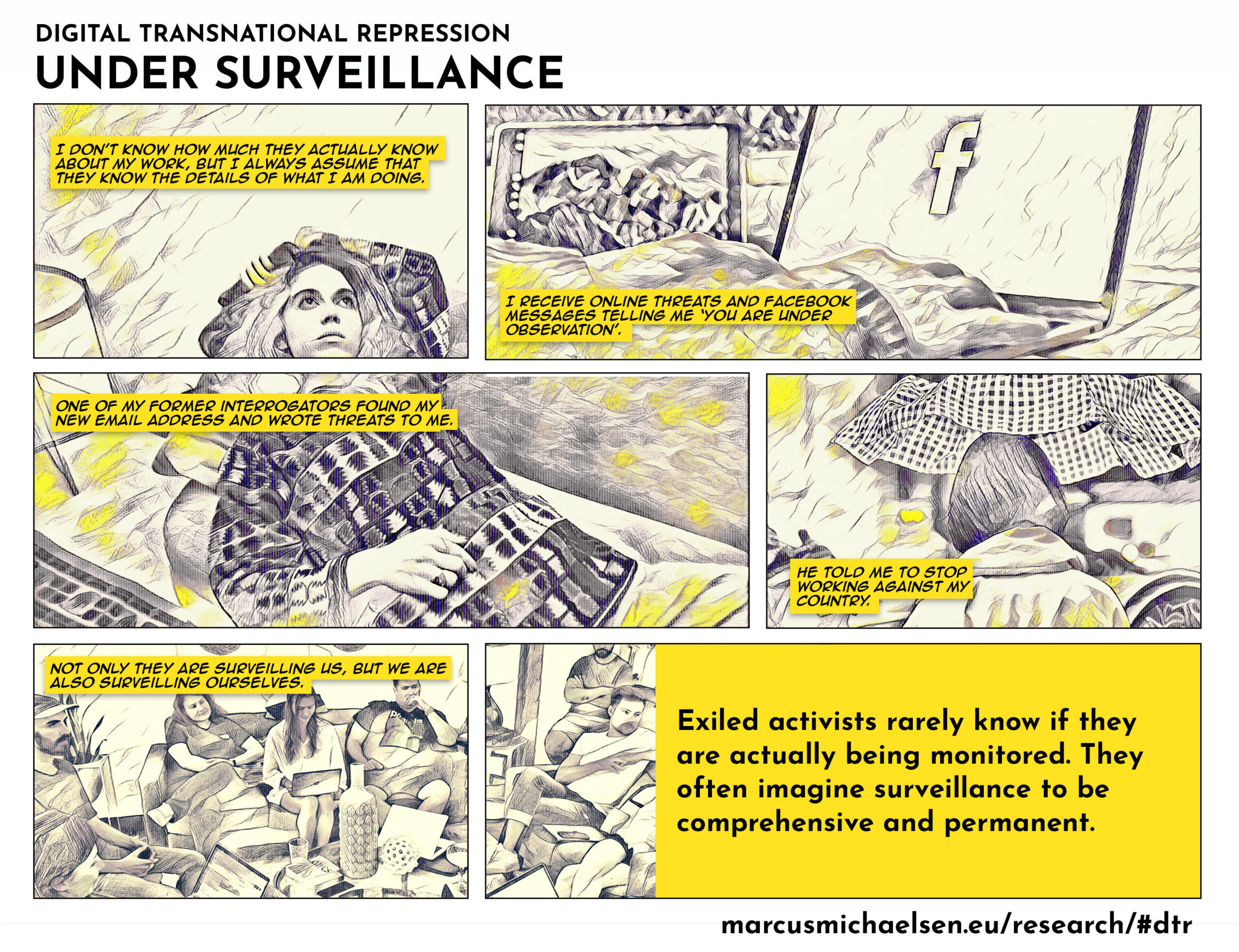

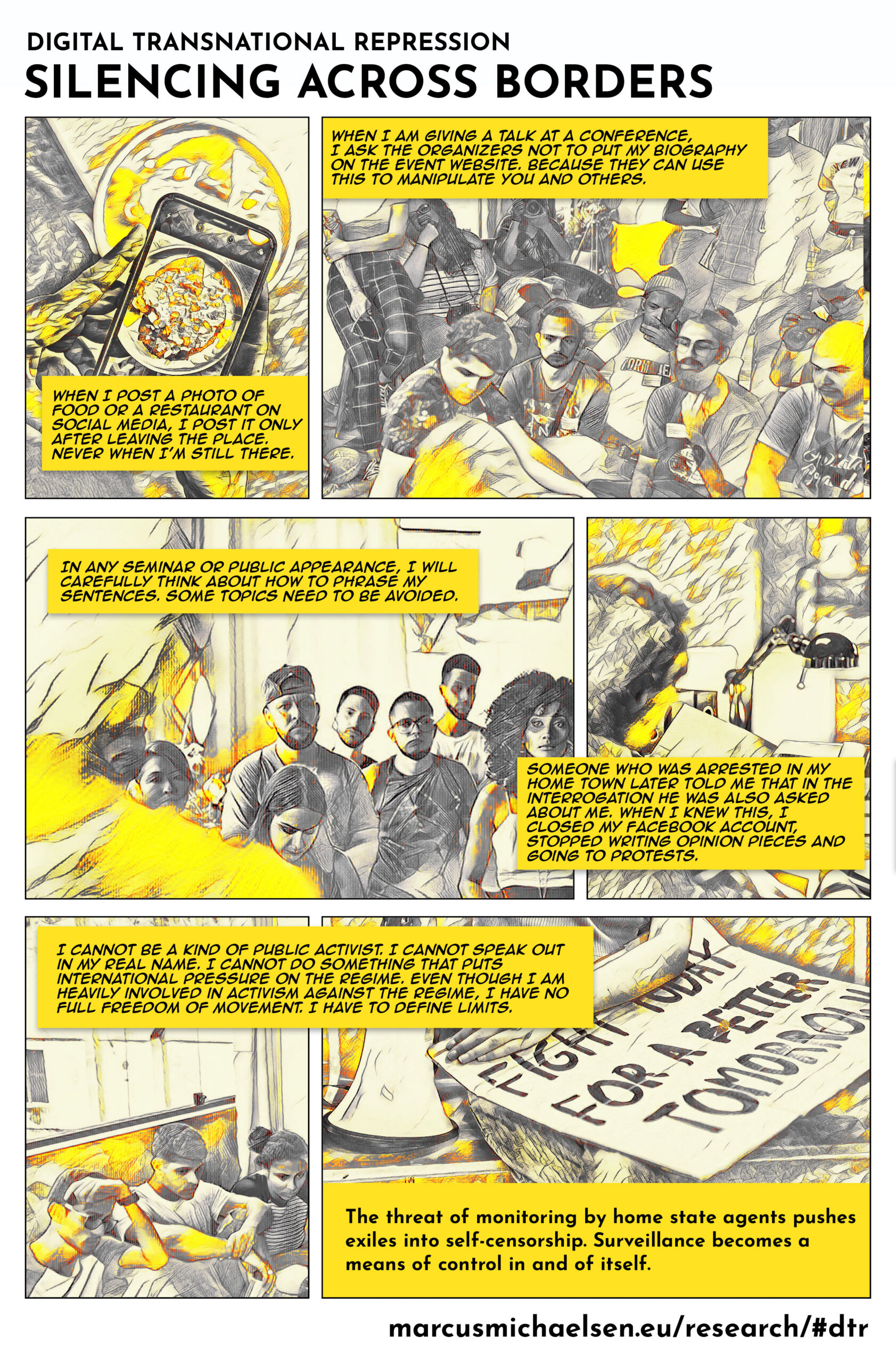

By relying on digital transnational repression, authoritarian regimes are able to reach deep into the lives of the exiles, wherever they are. Because digital communication occupies a central place in our everyday routines and we maintain intimate relationships with our devices, the effects of digital repression are immediate, disturbing and often very personal. In a series of graphic snapshots that I developed together with Nozilla, we use snippets from interviews with Middle Eastern activists to condense the feelings of uncertainty, fear and isolation experienced by exiles at risk of digital repression.

Authoritarianism in a Global Age

How do authoritarian rulers respond to global information flows, the movement of people as well as transnational networks of associations and non-governmental organisations? The 5-year comparative research project “Authoritarianism in a Global Age” at the University of Amsterdam investigated how contemporary authoritarian rule is affected by and adapts to globalization. One of the project’s key contributions was the idea of considering authoritarianism not as a form of governance bound to a specific nation-state and territory, but rather as practices of accountability sabotage. Authoritarian practices disable access to information or disable voice. They can occur in established democracies, at the subnational level, or in arrangements involving private companies and international organizations.

As a member of the project (2014-2017), my work focused on the ways in which authoritarian states control and regulate, but also benefit from the internet. Building on the idea that internet governance can be considered as a field of global power struggles, I approached authoritarian internet controls not only as a response to domestic dissent but also within the context of international relations. In a paper on the international politics of internet control in Iran, published in the International Journal of Communication, I showed how external challenges, such as cyberattacks, democracy promotion and the development of anti-censorship technology, stimulated the defensive and offensive capacities of the Iranian state for controlling internet infrastructure and usage. The paper was part of a special section on “Authoritarian Practices in the Digital Age” that I co-edited. In the prologue (that I co-authored with Marlies Glasius), the twin concept of digital illiberal and authoritarian practices was introduced to identify and disaggregate how three categories of threats in a digitally networked world – arbitrary surveillance, secrecy and disinformation, and violations of freedom of expression – can be produced and diffused in transnational and multi-actor configurations.

In another research axis, I started to investigate the methods and effects of digitally enabled transnational repression. My article on Iran’s exiled activists and the authoritarian state laid the groundwork for what has become an independent and long-term research program.

The “Authoritarianism in a Global Age” project built on fieldwork in seven countries, and our team wrote a book distilling our joint experiences and reflections. Research, Ethics and Risk in the Authoritarian Field responds to the demand for increased attention to methodological rigour and transparency in qualitative research, and seeks to advance and practically support fieldwork in authoritarian contexts. The book is accompanied by a comic strip series in which the fictional heroine Alice encounters some of the challenges discussed in the book.

Digital Media and Political Change

A techno-utopian view of the internet as a liberation technology has accompanied the worldwide proliferation of the web from the very beginning, culminating in the labelling of the Arab uprisings in 2010-2011 as ‘Facebook Revolutions’. Critically engaging with prevalent assumptions of the internet’s democratising effects, my PhD dissertation examined the use of digital media by civil society and political opposition in Iran. Building on in-depth fieldwork in Tehran, content analysis of original media sources as well as interviews with Iranian bloggers, journalists and politicians, I developed a more nuanced picture of the role that digital media has played in political change and mobilization in Iran.

I traced how news websites, blogs, and ultimately social media supported the gradual emergence of critical counter-publics. When the protests against the manipulation of the presidential elections erupted in summer 2009, Iran’s Green Movement was able to build on established networks and a culture of online information exchange to promote its collective identity and mobilize international attention. The findings of my research have been published as a monograph (in German) as well as in contributions to edited volumes, including Global Activism: Art and Conflict in the 21st Century, edited by Peter Weibel (Cambridge, MIT Press, 2015).

Wir sind die Medien

Internet und politischer Wandel in Iran

transcript Verlag

I have also coordinated and edited a collaborative (English/Persian) book project with a group of Iranian journalists, in which the authors describe their personal experiences during and after the controversial presidential elections of 2009, starting from the agitation of the election campaign and the initial protests up to the period of repression, arrest and exile that followed.

While living in Pakistan from 2006 until 2012, I had the opportunity to apply part of the theoretical framework I had developed for my PhD thesis to a research project for the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung, one of Germany’s leading political foundations. The report New Media vs. Old Politics investigated the possible contributions of digital media to a process of democratization in Pakistan, and the emergence of a more inclusive and tolerant space for debate and civic engagement.